REVIEW: Flat Isolation and the Banality of Surveillance: A Review of Japeth Mennes’ “Waltz” at 65Grand

Cover image: “Security Camera (Prussian, Red, Verona),” acrylic on canvas, 15 x 12", 2023. Image courtesy the artist and 65Grand.

REVIEW

Flat Isolation and the Banality of Surveillance:

A Review of Japeth Mennes’ “Waltz”

65Grand

3252 W North Ave

Chicago, Il 60647

April 14 - May 13, 2023

By Curtis Anthony Bozif

Brightly colored, geometric, and vaguely ironic, the pictorial hard-edge acrylic paintings by the New York-based artist and musician, Japeth Mennes, currently on view at 65Grand, recalling in their simplicity icons that function as universal symbols in signage the world over, are the kind of paintings that blow up on Instagram, but for lack of detail, nuance, texture or scale, fall flat when encountered in real life. But it’s not disappointment that I feel. More like resignation.

Upon entering the gallery, visitors are confronted with the glaringly blue, cartoonishly outlined shuttered window of Shutters (Cerulean, Oxide, Ultramarine); on a side wall hangs its smaller yellow sibling, Shutters (Yellow, Naples, Ochre). That the shape of the canvases match the shape and relative flatness of the things they represent brings to mind a standard art historical narrative: in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Jasper Johns, by painting inherently two-dimensional things like flags, targets and maps, broke through the art world’s Greenbergian obsession with “flatness” and “abstraction,” opening the door for the everyday to reenter painting in the form of Pop. Obviously different, Mennes’ Shutters are still aggressively frontal and, significantly, closed. Like the drawn accordion style shades in Window Shade (Oxide, English, Verona), they connote privacy, reclusion, sheltering in place, or the riding out of a storm.

Image: “Waltz,” installation view. Image courtesy the artist and 65Grand.

Nearby are the two Stationery paintings, each depicting what looks like a small stack of three-holed loose-leaf paper, begging the question, who writes anything in longhand anymore? Like the curiously rustic shutters, stationery feels like an anachronism. It’s in email that we find correspondence today, if it hasn’t already devolved to text or Twitter. Should we read the front facing blankness of the pages as a sign it’s simply disappeared? On his website, Mennes says his paintings “depict the balance of solitude and togetherness of our daily life and shared environment.” I’m dubious about “togetherness,” but I do find the “solitude” bit compelling. Or is it social isolation? A recent Gallup poll showed that the percentage of Americans who say they have no close friends increased from 3% in 1990 to 12% in 2021. Over that same period, Americans who say they have ten or more close friends dropped from 33% to 13%. What’s more, numbers like these don’t seem to have changed much post-pandemic. Theories behind what’s been called the “loneliness epidemic” abound, but almost everyone agrees the proliferation of smartphones and social media has something to do with it.

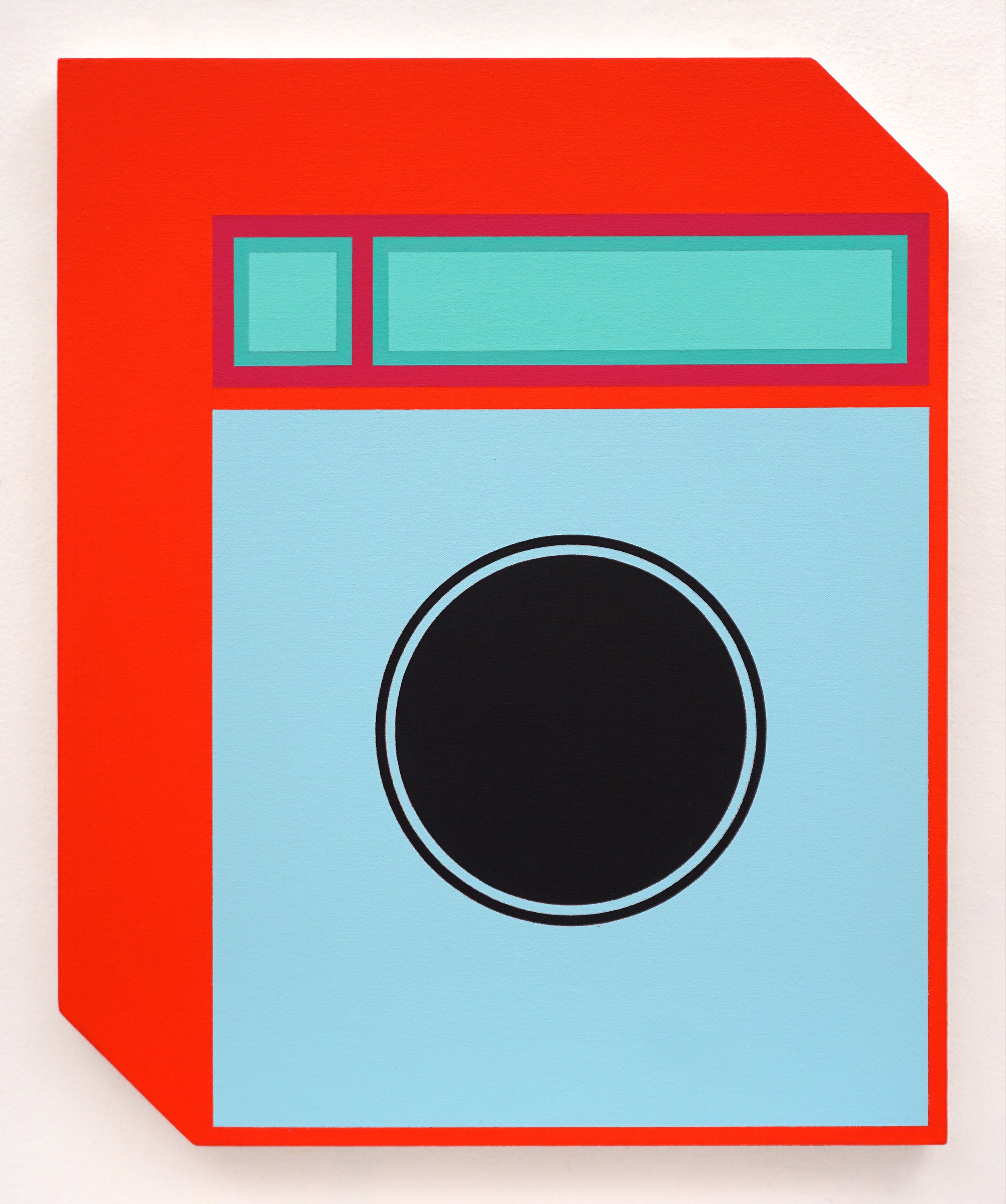

Image: “Laundromat (Vermillion, Magenta, Verona),” acrylic on canvas, 22 x 17" 2023. Image courtesy the artist and 65Grand.

There’s also a long wall of Laundromat paintings that, in their squarishness, repetition and opacity, make me think of the work of Josef Albers, an “Homage to the Washing Machine,” and confirm again, by the sheer variety of their combinations, that on the list of Bauhausian 2D design elements that includes things like line and shape, color is the most pervasive and easily deployed. Then it occurs to me that doing laundry, for a majority of people, is unpaid labor. Something most of us do, but would rather not, and certainly, if given the choice, would prefer to do in the confines of our own home. If you’ve ever spent time at a laundromat, then you know how the mesmerizing tumble and tick and drone of the wash machines and dryers, like so many spinning clocks, only serves to remind you you’ll never get these hours of your life back.

Friendly is the palette. The scale: polite. The subject matter, quotidian and relatively innocuous. The exception to the last part, however, are the two Security Camera paintings, hung conspicuously high in the corner of the walls; the most interesting pieces in the show. As is true of some of the Laundromat paintings, in the Cameras, Mennes opts for oblique, or parallel perspective over two-point perspective.

Image: “Waltz,” installation view. Image courtesy the artist and 65Grand.

Without vanishing points, all attempts to enter the space of the cameras go sideways. If there’s any depth to the show, it’s on the other side of the comic strip glassiness of those two gray lenses. Except, of course, between what’s in front and who — or what — is behind, the closed loop of the continually recording video camera does not discriminate. In the context of everyday things like washing machines and window shades, is the implication we should all get used to this? Or, that we already have? In a world of spy satellites, A.I. assisted facial recognition and the algorithmic mining, sale, and purchase of personal metadata by corporations — in a security state — privacy is a luxury, a privilege, it’s power. Yet, it’s hard to imagine anything more boring than security camera footage. Which, if Big Brother is doing its job, is precisely the point. By capturing the nothing-to-see-here banality of surveillance culture, the Security Camera paintings cast with their gaze an ominous shadow over an otherwise shade-free exhibition.

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.