PUBLIC UTILITY: The Chicago Arts Census, “An Introduction to Abundance”

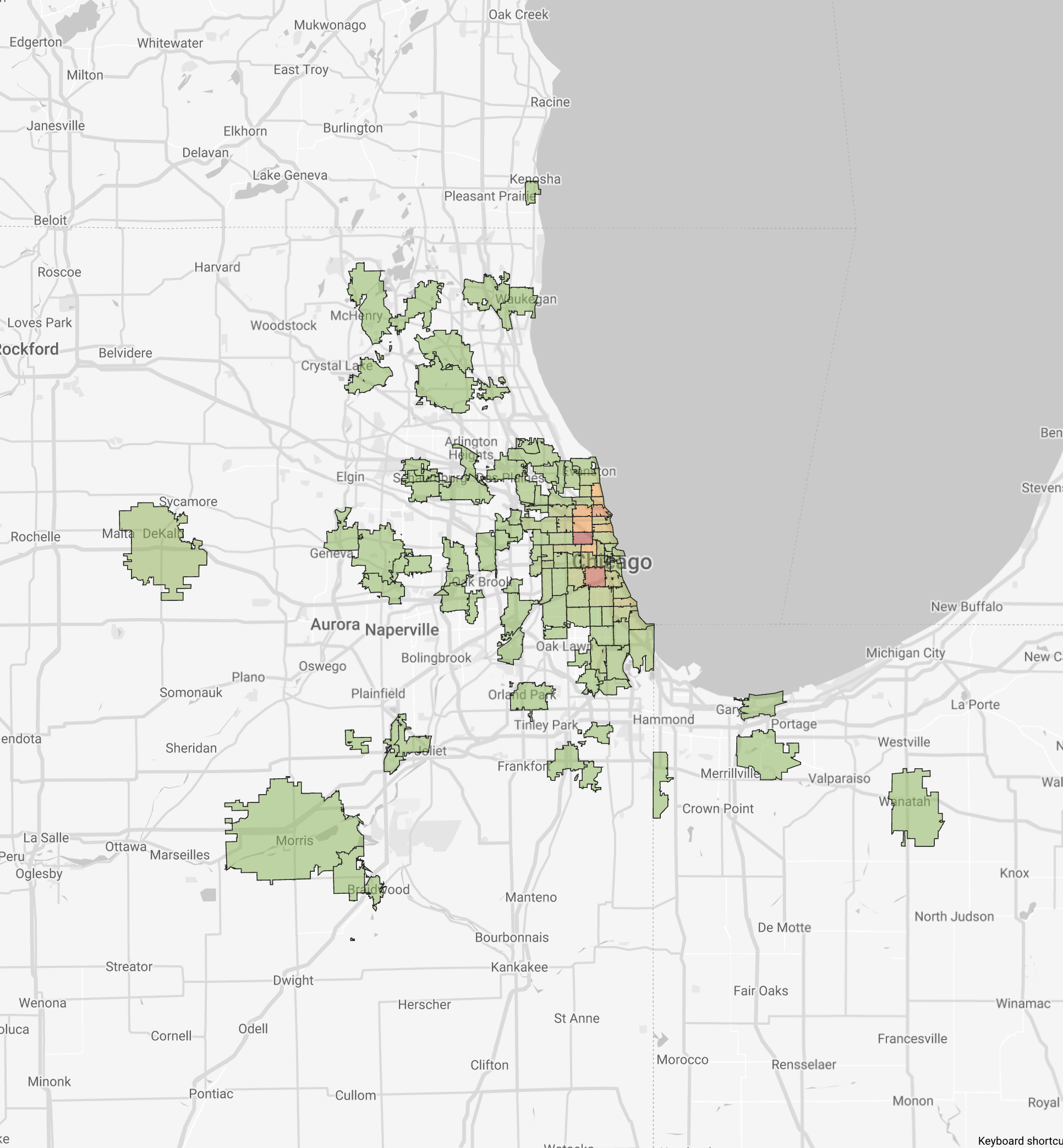

Chicago Arts Census map of respondents.

At Bridge, we have long thought of the work done when people band together for collective action through social movements, mutual aid organizations, and not for profits (despite the legitimate differences between them) as critical to our collective well-being. So we have created PUBLIC UTILITY as an occasional feature to highlight the work of those whose work we find informative, that pushes back against institutional hierarchies and elevates the public dialogue to be more inclusive and welcoming of traditionally underrepresented voices, dissidents and that may help inform critical, often neglected issues in the current public discourse.

This feature will offer a platform for these coalitions to present their case for existing, their central arguments and supporting evidence in hopes of finding the change that their constituencies wish to achieve in society. Artists, too, after all, use the same tools when needed, of urbanism and activism, community organizing, legislative action and remaking of political structures, public policy and institutions. We are launching this new feature simultaneously here at the online magazine in partnership with the Chicago Arts Census, to provide a platofrm to present their findings, and in our upcoming volume of the Bridge Journal, with a profile of the work of CivicLab, whose work to illuminate how tax-incremental financing (TIF) funding as a widely-adopted, and deeply flawed, channel for public funding. -Michael Workman, Editor

PUBLIC UTILITY

The Chicago Arts Census

By Kate Bowen, Alden Burke, Stephanie Koch, Tiffany Johnson, and Adia Sykes

“Any understanding of work and organizing within the arts must be powered by a commitment to collective wellbeing. What does organizing and action accomplish if people remain vulnerable, forgotten, left behind? ... We must be compelled by a holistic understanding of how art workers are both formed through and continuously shaped by the large-scale forces that dictate our survival.”

– Annette LePique, “Lion Cages and Lilac Fields: From Chicago Stages to Basements, Art, Work, and Other Pandemic Songs,” Sixty Inches from Center, 2021.

After an introspective reflection on your labor, livelihood, and well-being, the Chicago Arts Census asks its final question: “Imagine an abundant future: What does a full life in Chicagoland look and feel like to you? What do you need to thrive as an arts worker in the Chicagoland ecosystem? What do you have to share? How can you contribute to other’s ability to flourish?”

“An abundant and free future, in the words of Nina Simone, is "no fear." I'm talking no fear of houselessness, of joblessness, of lack because either the systems that exist have been so radically changed or we, as a community, have constructed alternatives. Most importantly, that shift towards realizing a liberated future will start with and be guided by those who are the most oppressed under the systems that exist, because once those populations are free, all of the remaining structures will, undoubtedly, have to fall.”

“I imagine a Chicagoland where artists are able to pool resources and support one another, rather than be pitted against each other in a race for funding and support from gatekeepers and government agencies. I imagine a place where housing and healthcare are affordable enough that artists don’t need 3+ jobs to stay afloat and where artistic space is subsidized to make the rentals affordable.”

“I can find joy in many instances, and have honed my ability to cultivate joy and wonder for the smallest of instances; to the point where those things have become a kind of protection practice against the harm of our current nation-state. I believe in change and radical imagination and possibility.”

“Affordable housing near loved ones and support systems.”

“I would need to be paid fairly for my artistic work. There are a lot of opportunities currently to show and participate within artistic work but not a lot of compensated opportunities. If I were compensated properly for my artistic work at the level that I am trained to perform, I would then be able to create opportunities to compensate other people in the art industry.”

“[Being able to] contribute to others' ability to flourish relies on my capacity and desire to grow and to love.”

These quotes are a small sample of over 2500+ experiences generously, honestly, and brutally shared over the course of 210 questions created by and with art workers of Chicago. As Lead Organizers – Kate Bowen, Alden Burke, Stephanie Koch, Tiffany Johnson, and Adia Sykes – we worked to collect the voices and lived experiences of our peers because a complex and intersectional account of art workers does not exist. We are a missing dataset. How might the language of data and its different embodiments shift how accountability and support structure in the arts sector? Data on its own isn’t enough. But data combined with context, maps, and stories become information and knowledge. Information and knowledge shared, discussed, and critiqued by a community transform into wisdom (Toni Morrison, The Source of Self-Regard).

With a focus on imagination, solutions-based approaches, and nuance, the Census team is synthesizing thousands of information sets to concretize the realities, needs, and desires of art workers in Chicago, as well as bring attention to the mutual and collaborative systems of support that exist outside of main funding streams. The intention of the following early-stage synthesis is to propel coalition building with organizations and individuals working to change policy and imagine new futures. This includes working with incoming Mayor Brandon Johnson on his Arts & Culture Policy plan.

Building the Census: A By/For Methodology

The Census adopts a bottom-up approach of grassroots community organizing and community-centered design — a strategy to build collective power by identifying shared needs. The Census and its accompanying public programming and publications intend to raise city-wide coalitions needed to align specific and collective interests and influence change over time.

Practices of collective authorship, care, and transparency guide all research, testing, data collection, synthesis, and distribution processes. The project includes ongoing working groups, roundtables, and public programming to create the Census and establish:

Scope of work, format, form, and questions for the Census

Distribution methods of the Census inquiry

Translations of the Census data into a series of written reports and mapping systems

Toolkits on how the information from the Census can be shared with others for use, and what form and timeline of sharing make sense in relation to the information received, such as a directory of resources for artist workers

Interviews with stakeholders

Bibliography and literature reviews of relevant resources

Programmatic conversation around the project goals and findings

As such, the Census is co-authored with art workers across sectors in three Census Committees – Steering, Research, and Peer Review – representing a breadth of communities, disciplines, organizational affiliations, and zip codes. Committee members are integral to the creation, dissemination, and evaluation of the Census – they are the locus point in which data, information, knowledge, and wisdom collide to give life and shape to a tool that hopes to serve their larger communities.

This approach is responsive to the conditions of real-time learning while creating a common understanding of our shared practices and behaviors. It emphasizes democratic notions of expertise, transparency, and community building. Co-creation is a core value we fostered throughout creating and synthesizing the Arts Census. Additionally, the project environment is framed as a learning opportunity for everyone who participates, positioning learning and collaboration as a social and necessary community-building activity rather than the effect of a technical task.

Synthesizing Sets: A brief overview of what we’re finding

The following outlines our initial thematic findings from processing, synthesizing, and reflecting on the quantitative and qualitative outputs from the Census collected from November 2021-June 2022. All quotes come from census participants who elected to have their stories shared with the public.

A lack of support and resources leads to volatility in quality of life

In our initial analysis of the Census responses, we saw what we describe as volatility in the data. We define volatility as unpredictability with a frequency of change taking place over the span of a year, at minimum, indicating a lack of consistent or predictable conditions over time. Contributing factors include inconsistent wages, frequent housing transition, unpredictable number of paying jobs, different tax filing types, changes to insurance, and general uncertainty about job security and resource availability.

"I am desperately stressed out, tired, and overworked, because saying yes to everything is the only way that I can cover my costs with room to grow financially and have a safety net. The safety net is key because my job security is a constant source of stress for me.”

“Under-employment and lack of adequate health care led me to roughly 6 years of accrued credit card debt. Medical expenses often exceed the cost of my apartment and studio rent combined. I took a part-time museum job early on to pursue my goal of working as a curator and researcher, but without a second job lined up to support myself, I took out a credit card and used it to pay my medical expenses for years, only paying the debt back last week.”

The lack of consistency is a major factor contributing to the volatility of art workers' lives. Many arts workers are paid on a project-by-project basis and/or paid work is contingent on grant funding, leading to fluctuating incomes that are difficult to predict and plan for. This uncertainty makes it challenging for art workers to manage their finances, maintain a stable living situation, and plan for the future. Additionally, the lack of consistent wages makes it difficult for art workers to access essential benefits such as health insurance and retirement savings, further exacerbating financial instability.

Financial instability contributes to instability in other key areas of health and well-being, such as housing, food access, personal care, development, and opportunities to participate as a member of a community.

“Finding ways to navigate poorness is creative mastery.

“I'm often finding ways to pivot and shift my desired way of working to fit into this current financial condition. Additionally, sometimes the mental burden of maintaining or seeking work/finances takes away from being able to lean in into artistic pursuits. “

Arts organizations and their workers often face precarious funding structures, which can vary yearly and be subject to the whims of public opinion and political priorities. This creates a climate of uncertainty and instability for art workers, who may experience periods of unemployment or underemployment as a result. In addition, funding disparities based on race, gender, disability, and geography are a persistent problem, with marginalized communities often facing even greater obstacles in accessing resources and support. These factors contribute to a lack of financial security for art workers, making it difficult for them to sustain their work and livelihoods in the long term.

A majority of arts workers make less than 35k and are unfairly compensated for their labor

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, between 2017 and 2021, the median household income was $65,781.

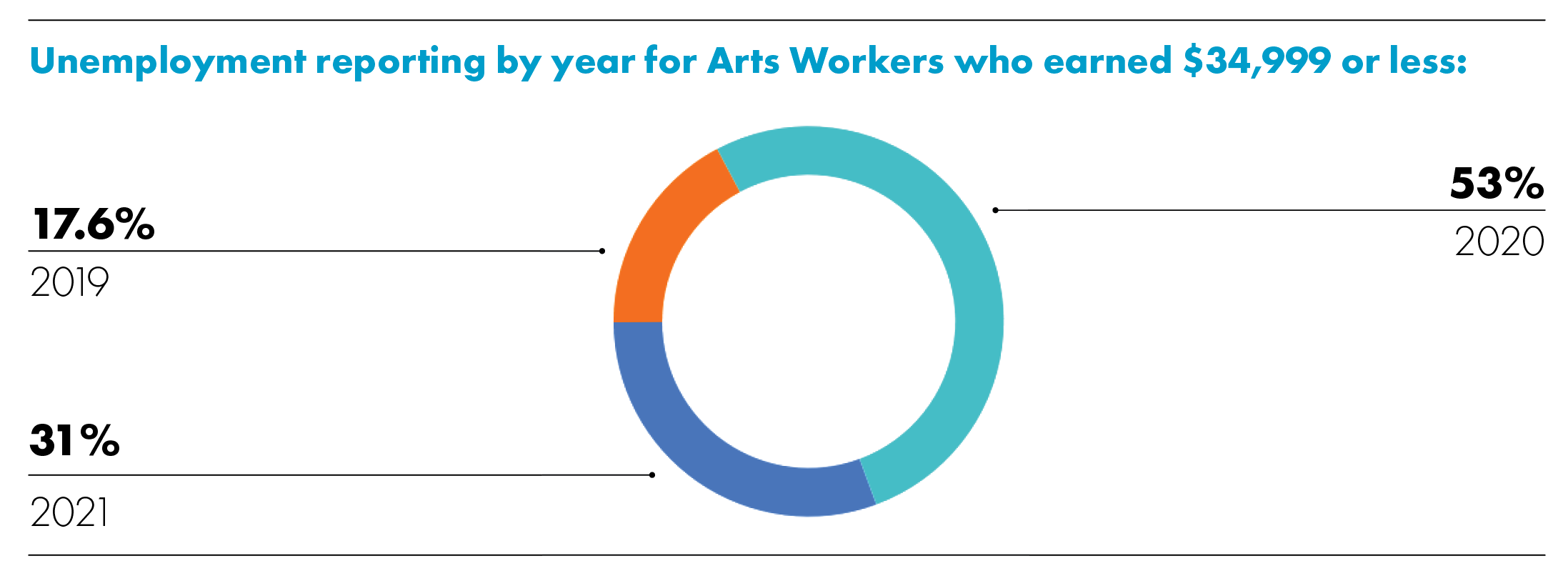

The Chicago Arts Census gathered information on annual income earned in 2019, 2020, and 2021. We wanted to understand how art workers organized their living before the pandemic, during quarantine, and after quarantine. From respondents to the Chicago Arts Census, the median total income in 2019 ranged between $30,000 to $35,000, with 28.6% reporting limiting their income to maintain government benefits. In 2020, the median total income remained in the same range, with 24.22% reporting that they restricted their income to maintain benefits. In 2021, the median total income had a small increase from $35,000 to $40,000 and with 23.36% reporting to limiting their income to maintain benefits.

According to Zillow’s data, the estimated average rent in Chicago is $1,925 as of April 2023, and respondents to the Chicago Arts Census shared that housing is their top monthly expense. Multiple art workers shared that they had to move further away from work and community or drastically reduce their artistic practice to focus time on earning to afford housing:

“I have generally spent over 50% of my income on housing since I moved here. I would never have been able to afford to start my own business if I didn't have an anti-capitalist friend who offered me an incredibly cheap lease in her building (as her way of fighting gentrification in the neighborhood). Prior to that, I was renting a tiny studio apartment for the same amount of rent, where I could not possibly have fit a loom (or afforded to rent a separate studio space).”

Although approximately 97.5% of respondents shared that they had health insurance through their employer, family, the Healthcare Marketplace, or government assistance, enrollment did not mean coverage that was affordable and comprehensive:

“Under-employment and lack of adequate health care led me to roughly 6 years of credit accrued credit card debt. Medical expenses often exceed the cost of my apartment and studio rent combined. I took a part-time museum job early on to pursue my goal of working as a curator and researcher, but without a second job lined up to support myself, I took out a credit card and used it to pay my medical expenses for years, only paying the debt last week.”

Among the top monthly costs for art workers, respondents shared that family expenses, including child care, are third. According to the Treasury Department, childcare is unaffordable for more than 60 percent of families who need it. These costs place constraints on both how art workers organize their living and how they devote time and energy to their artistic practice:

“Being a parent now for the last 14 years has affected my relationship with my job and my ability to progress in my artistic practice due to the unequal expectation as a woman to take on much more of the domestic and parenting responsibilities. A big chunk of my time is used to prepare meals, clean and organize our home, prepare children academically and personally for their day or for the world, extra-curricular learning and support for my children and of course in their early years - breastfeed and nurture them. The lack of support for mothers especially and lack of childcare as well as a salary for mothers who do unpaid labor at home impacts greatly women who are trying to raise their children, practice their art and work in and outside the home.”

For many art workers, the cost of living is not met with a single income that can afford housing, transportation, childcare, groceries, taxes, and healthcare. Rather it is a complex and dynamic negotiation with multiple streams of income and debt, exchange of resources with family, coworkers, and friends, and flows of public and private support.

Volatility, resources, and community are interconnected and affect well-being

The Census stories and data reflect the impact of larger socio-political concerns on our lived experiences, including racial justice, affordable healthcare, labor rights, gender equity, the nonprofit industrial complex, capitalism, elitism, and white supremacy. The pandemic further revealed the precarity of the arts ecosystem and the long-standing challenges for those who work in it.

Art workers often work for low wages, juggle multiple jobs, and lack health insurance. We are intermittently navigating unemployment and moving every year. We are tired. We feel the strain and scarcity of resources in our everyday lives, yet what we feel and need is continually unaddressed within existing structures of support, whether nonprofit or for-profit.

“Most often in the jobs I've taken, I feel as though I have to consistently settle for less than ideal conditions and compensation for my labor. I am a black woman who tries to advocate for others and all, but because of stigmas and lack of resources offered at the jobs I feel comfortable enough taking, [the jobs] often offer me fewer resources than I need. Many of the jobs I've had permanent and temporary/contracted, I've experienced racism, sexual/gender bias, underpay, and lack of care.”

“Largely anti-capitalist oriented, I have never wanted a job that requires me to work full-time. This was my choice in order to maintain an energetic ability to give energy to my artistic practices and as an act of radical reimagining. In that decision making, I chose to sacrifice comforts (but really necessities) like the possibility of sufficient healthcare or income, and allowed certain resources to be supplemented in other ways.”

The Census does not intend to divorce the art worker's life and labor, their work from their personhood, but instead show how it is all interconnected. From institutional resources to community support, access, and stability in these areas leads to better well-being, which leads to artistic contribution, participation in the arts community, and vivid engagement more broadly.

“At this time I essentially feel as though I'm building much of everything from the ground up. For the past few years I've grown into my skill of grant writing and arts-application process – however I've yet to reap as much benefit from that area of expansion that I need. I'm doing my best to make changes accordingly and be even more patient in my pursuit of care and creative autonomy.”

What’s Next: Building the Coalition

Whether you’re poring over 2500+ survey responses, filling out your tenth grant application, sending your boss another text about being compensated on time, laughing after an opening, or meeting with your colleagues to whisper about the possibility of unionizing, Chicago’s art ecosystem is brimming with potential. But we are finding that possibility and potential continuously tamper at every level of engagement in the arts ecosystem.

We want the power to determine and name what constitutes support to be determined by those living the experience of an art worker. The Census team will continue to synthesize findings and publish them on our website and other partner sites, and create public programming to push these conversations into actionable policy outcomes.

Calls to Action

Take the Chicago Arts Census – it’s open and we want to hear from you!

The Chicago Arts Census is part of a lineage of thought and advocacy for a healthy arts ecosystem. We are guided by what adrienne maree brown and Sonya Renne Taylor describe as the river: ideas that don’t belong solely to us, but instead, we find ourselves inside of that which is already in the world (from their conversation Permission to Imagine: Radical Love & Pleasure). To learn more about our river, check out our full bibliography here.

Get in touch: Reach out to learn more, connect, or partner with the Census by emailing census@acreresidencry.org

Follow the Census on Instagram

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.