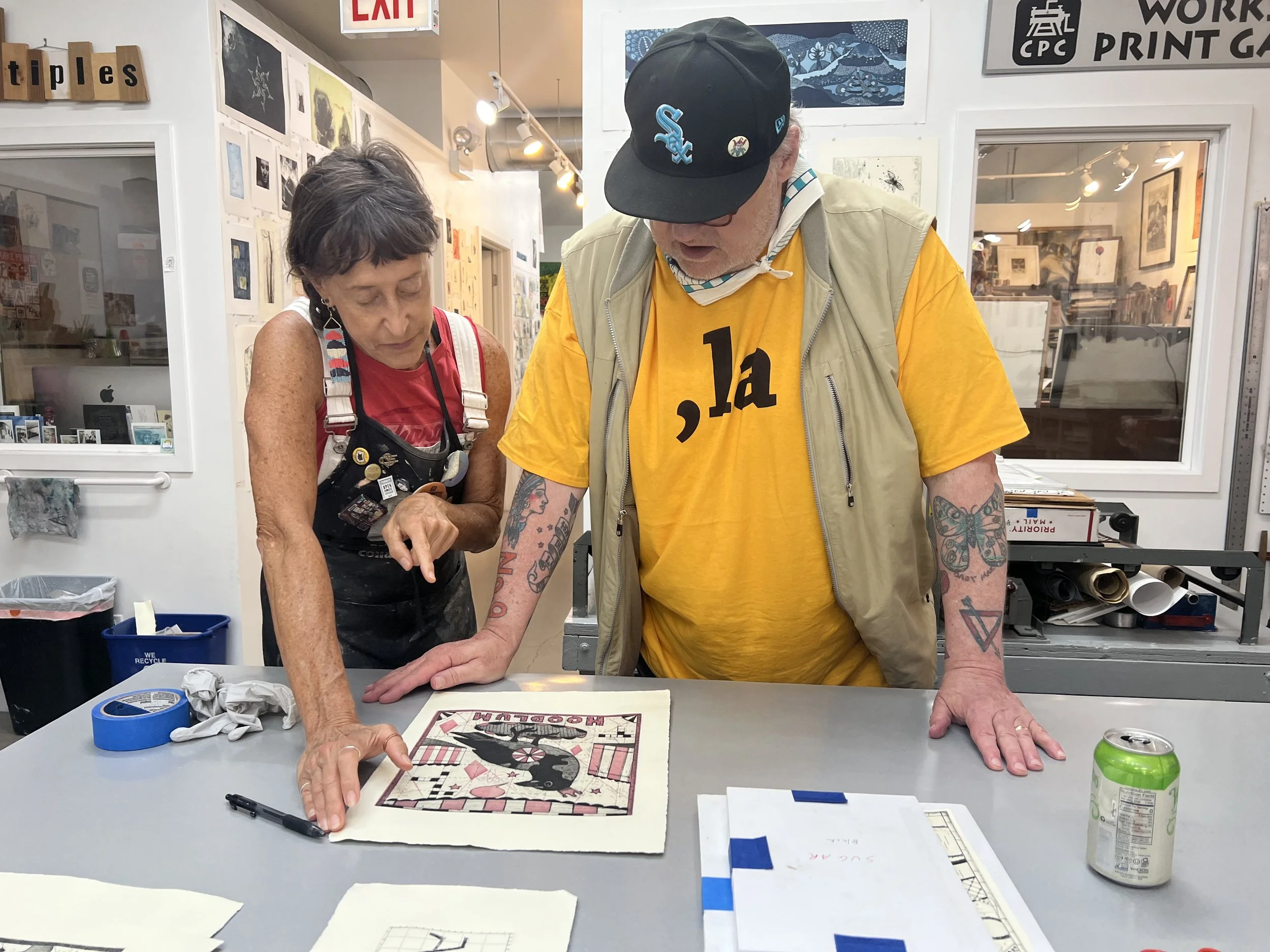

INTERVIEW: Chicago Artist Tony Fitzpatrick Talks Chicago Art

Image courtesy of Michael Workman

Chicago artist Tony Fitzpatrick has long been recognized as an outspoken advocate of the kind of self-reliant, no-holds-barred approach to art-making that has long been recognized as the bold signature style of both Chicago art and Chicago artists. Bridge Magazine recently caught up with Fitzpatrick at his studio on Damen Avenue to discuss the city’s art culture, the failure of its art institutions and gallery systems to connect artists with the wider world.

By Michael Workman

BRIDGE: What can Chicago artists do to reach a wider audience?

Tony Fitzpatrick: One of the little secrets is that once you give something to a charity the people who didn’t get it for the auction find a way to your studio and buy something. You know, giving stuff for charity is very good for business. It’s done wonders for me. People come and find you. I’ve also made it a point to be easy to find. I think to survive as an artist in this city, you better be easy to find. I also think this notion of artists sitting around suffering up in their garrets is ridiculous. If artists in Chicago wonder why they don’t make a living, a good fifty-percent of it’s their fault.

They don’t reach out enough?

They make themselves inaccessible, you know. One of the simplest tricks in the world to get your work seen if you’re a young, emerging artist is take the best piece that you have, make a postcard of it…have a pro shoot it and make a postcard of it, buy that Art in America guide to all the galleries in the U.S., go through it, look at the galleries you think you might be a fit to and send them a postcard. Don’t call them, don’t walk through the door, don’t throw your slides on the desk. Send them a postcard, they’ll look at it and decide. That way you leave the dealer’s discretion intact and they’ll have a look at one of your images.

If they like it, they’ll call you.

I do this every six months. Every six months I make a new postcard and I send it out. I don’t need more representation. We do it anyway. We do it just in case we missed somebody in Europe, or we missed somebody where there is an opportunity. Part of it this whole thing is that it’s a business and you have to learn to do business and artists here particularly… I think one of the smartest things I heard this summer was how Andrew Rafacz and Keith Couser (of Bucket Rider Gallery) were staying open for August and promoting their show. They’ve had people in, they have a few artists that people are looking at right now and they did the right thing. The secret is being accessible when nobody else is.

Image courtesy of Deborah Lader

Do you think it’s important for a gallery to be open year round?

I think the Internet changed everything. I think it made the art world much more accessible. I mean, on a keystroke you can now see what everybody’s got in all of their galleries. So the idea that “Oh, don’t do this in Chicago because it will be perceived as regionalist” is ridiculous. The art world has shrunk and it has flattened. It is now accessible to anybody with a PC. You can go see virtually whatever you want in the art world. The information has been democratized, so what we have to do now is put our best foot forward when it comes to having shows. Places like Western Exhibitions and Lobby Gallery, places like that have made it a point to be accessible, have made it a point to always be busy when everyone else is on vacation.

A lot of people perceive summer shows as the outlands.

I think that’s ridiculous. Pierogi is one of the models I use for galleries that are doing something right in New York, and they’re open all year round. And they throw a big opening in the summer. The summer show is one of those New York affectations and “OK, I’ll throw a group show up for the summer while I’m off tanning my fat ass off in the Hamptons and if any off this crapola sells, maybe we’ll look at this guy for a show down the road.” The smarter galleries, the more insurgent galleries have looked at the summer as an opportunity when A), a lot of people are travelling and a lot of people are travelling to Chicago, and B) they will be accessible and put their best stuff up.

So you see Chicago as a summer place?

Oh yeah. A lot of people come here, they walk through the door everyday. I do a lot of business in July and August.

You do? That’s local people, or are you getting tourists?

People from out of town, people who… my New Yorkers who, all season long, are in New York looking at art, summertime they’ll come here for BluesFest or some of the summer things, and yeah, they’ll walk through the door.

Let me ask you this, since we’re talking about Chicago as a destination, what do you think about the current state of the gallery system? In particular, the kind of smaller galleries like we mentioned: Western Exhibitions, Lobby?

Those are the ones I hold out the most hope for.

Explain.

Well, there’s this system that’s almost feudal in its construction, where one art dealer can represent twenty-five artists and make a living off them, but none of those twenty-five artists can make a living off that dealer. There’s a very serf-like mentality that gets imbued in the artist. What I’ve always done, and what I will continue to do, is look out for my own best interests as an artist. I have a public studio where people can walk through the door and buy these etchings. It doesn’t interfere with my gallery relationships, because they only handle one of a kind work. But my printmaking and etchings are accessible to anyone who wants one. Somebody can walk through the door here and for two hundred dollars get something really lovely. They can also spend eighteen hundred dollars and get something else really lovely. I was represented by a gallery in Chicago, but I have since given up my representation.

Do you want to name who that is?

It’s not fair to them, they’re not here to speak for themselves. Let’s just say I can do more for myself then they can. What artists have to realize is that with the Internet, with the ability to JPEG your images for a hundred, hundred-fifty collectors… come here, I’m going to show you what I do. I’m going to show you what I do every time I make a piece. What I do is, we scan it. Get it into PhotoShop, and (my assistant) Mike does all that because I’m a moron. This piece went out to two hundred collectors yesterday. I finished it yesterday. It will be sold before tomorrow. The dealer will probably sell it. I have a database of two hundred collectors and they’re in my address book. All I do is attach the JPEG to their address and it goes out to them. If I hear back from them, I give them Joe’s information and Joe finishes it for me. It’s just something artists can do for themselves. And another thing is, I don’t want to come off like dealers are strictly the bad guys. They are definitely the bad guys…believe me, they are. But they’re not alone in what’s fucked up. What’s fucked up is that artists do not know how to act in their own best interest. This invention (the Internet) made it significantly easier for artists to make a living.

Image courtesy of Michael Workman

Let’s draw that out a little bit and explain, you know, to say that they’re the bad guys and then to have this other technology…

They sell a painting, they pay the artist their fifty percent, which—by the way—the Mafia doesn’t get fifty percent. They go home and open a bottle of Cabernet, and that’s the end of the day. What about the larger responsibility? What about their responsibility to say to the institutions here, “this is who I have, this is who we should be celebrating. I want to get this front and center. I want to take these artists and put them into the dialogue and put them front and center in the discourse of what’s happening in art in this city right now.”

Make connections for them.

Exactly. Now… first of all, there’s a reason that can’t happen. The institutions here aren’t particularly interested in showcasing Chicago art. Their charter, their job is to get art from all around the world and bring it here. Fair enough. It leaves a huge void. There needs to be an institution that examines the artistic activity here, not only what’s happening right now, but for the last hundred and fifty years, and to then ferment the ground for art to be made here tomorrow. When my show opened in Brooklyn in January, I walked down Bedford Avenue and I ran into three people who used to live in Chicago and I listened as they told me how they felt like there wasn’t an end game for them here. So they moved half way across the country. They moved halfway across the country to pay double the rent because they thought they stood a better shot in Brooklyn

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.