REVIEW: Yudori, “Raging Clouds”

Cover, Raging Clouds by Yudori. Image Courtesy Fantagraphics.

REVIEW

Raging Clouds

By Yudori

Hardback ($34.99)

Fantagraphics

By Ryan Rothman

Despite the two women embracing on its cover, looking wistfully into the distance, Raging Clouds is not a lesbian love story. It’s not meant to be. Instead, it thrives in what South Korean comic artist Yudori calls the “beautiful chaos” between straightness and queerness — an intimacy that resists easy labels, where desire exists alongside duty, survival, and social hierarchy.

Masterfully challenging Western notions of queer liberation, Yudori’s debut graphic novel seems anything but amateur. At the center of the period piece lies a Dutch housewife, Amélie, shackled by a loveless marriage and 16th-century patriarchal norms. Fascinated by physics and the mechanics of flight, she forms an unlikely partnership with her husband’s enslaved mistress, Sahara, as they attempt to design a hot air balloon capable of carrying them both to freedom.

Amélie and Sahara’s unfulfilled romantic tension across class and racial lines drives Yudori’s exploration of female, queer, and sexual liberation. Guided by expressive illustration and poignant dialogue, their collaboration fizzles into a historically accurate – and lackluster, for those seeking a fluffy lesbian romance – end to argue for the subjectivity of freedom and empowerment in marginalized identities.

Image Courtesy Fantagraphics.

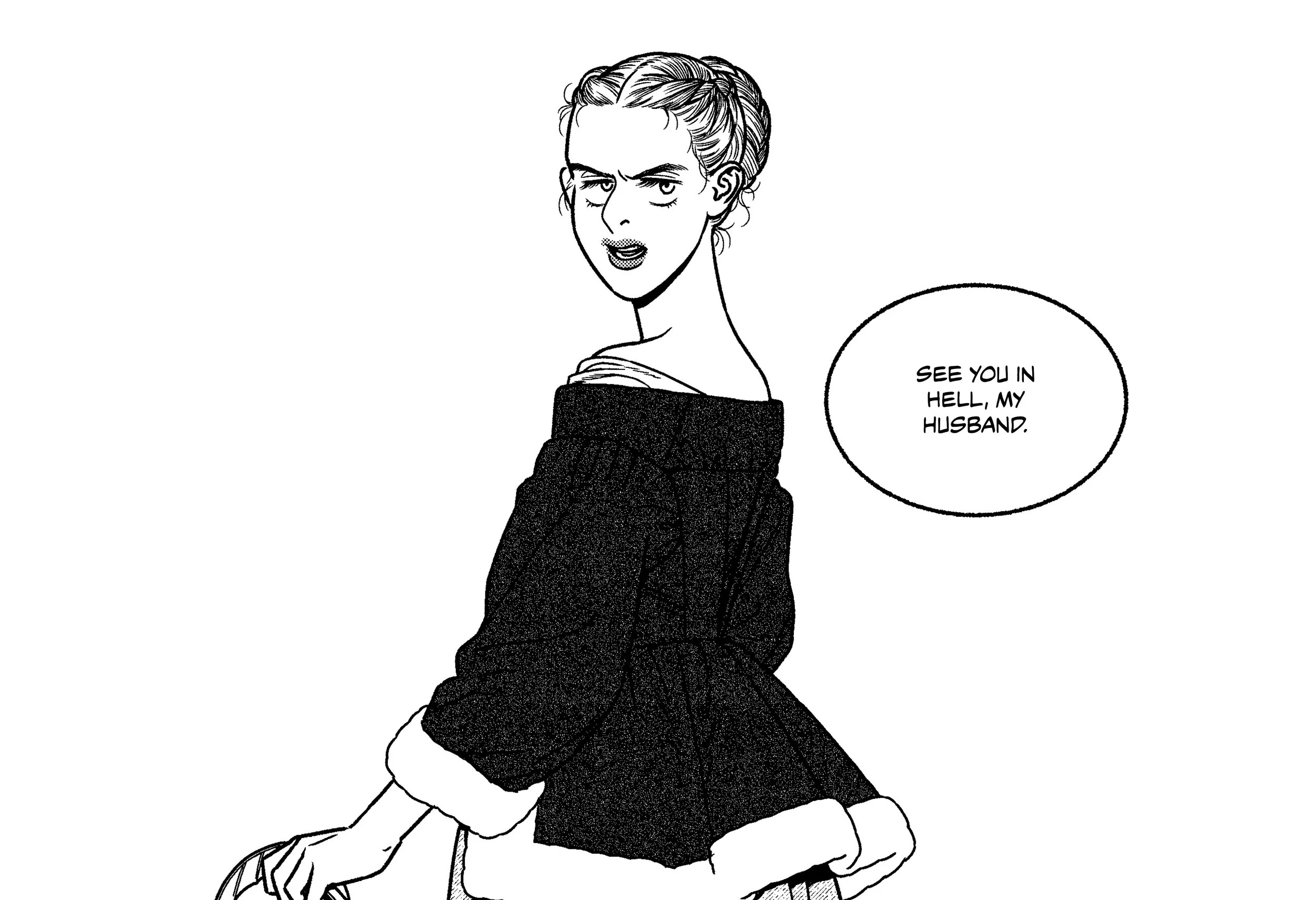

Raging Clouds begins with a classic formula: smart female protagonist born in a time when women aren’t supposed to be smart, leaving her an intellectually unfulfilled homemaker. Yudori delivers the expected amount of feminist one-liners for such a story, satisfyingly witty despite the fact that rich white women lamenting married life stopped being revolutionary at least ten years ago. “You leave me alone with my own vice, as I leave you to do whatever you like with your slave,” Amélie responds to her husband, Hans, after his up-teenth attempt to quell her scientific experimentation (or as he calls it, “sorcery”). “See you in hell, my husband.” Equally expected yet satisfying is the disastrous result of his later appropriation of her and Sahara’s balloon — both ironic and successful in liberating the two women, just not in the way Amélie planned.

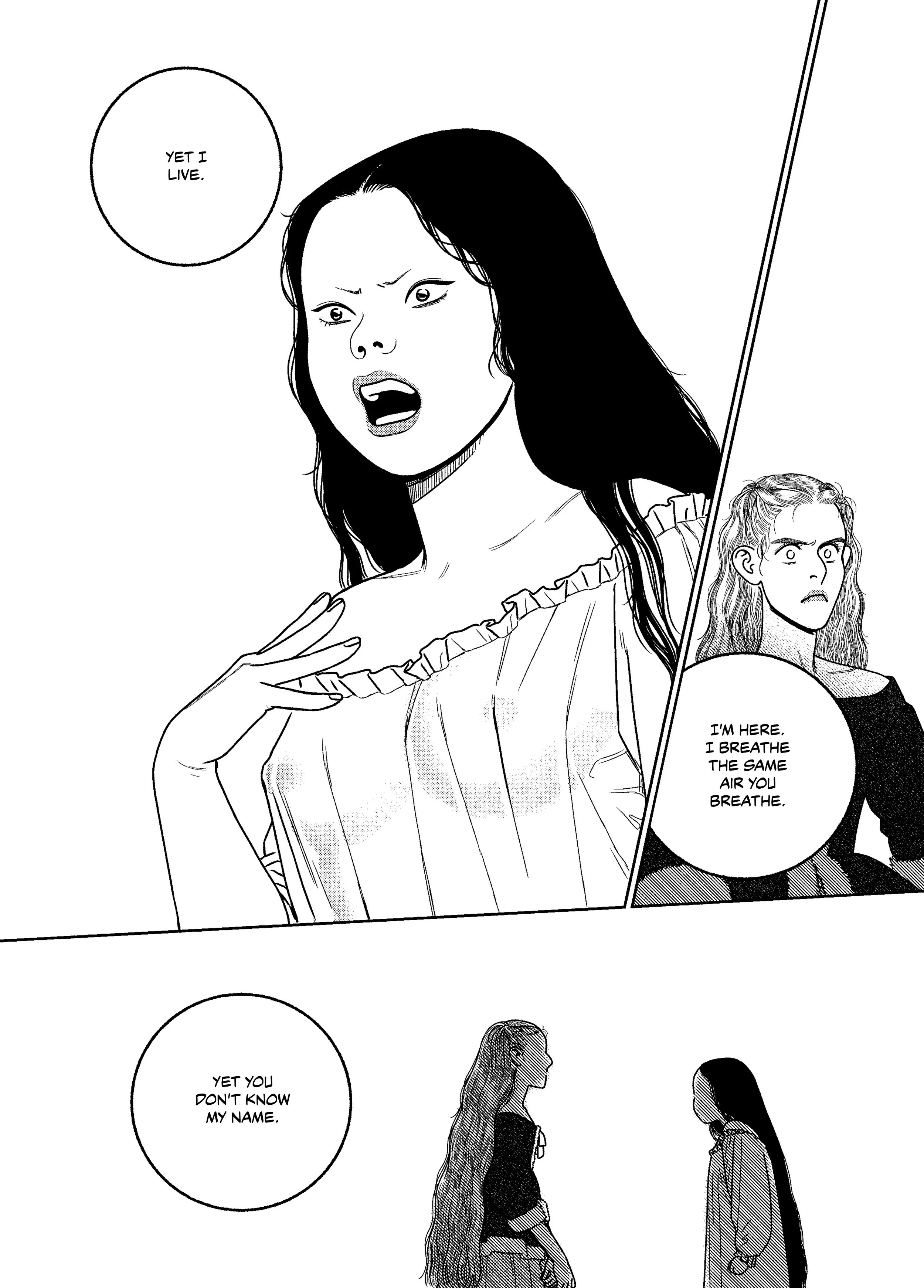

However, in exploring the racial and class differences between Amélie and Sahara, the story moves beyond a typical feminist period piece and explores the privilege necessary to pursue independence, as well as the subjective nature of female freedom. Each woman’s social positioning defines their view of and relationship with Hans: to Amélie, he thwarts her intellectual pursuits and chance at real love; to Sahara, he mercifully provides the basic needs and safety she would otherwise lack. Amélie struggles to accept the latter perspective, alternating between jealousy and pity for her husband’s mistress and imposing upon Sahara her own dreams of escape.

“Do you ever want to go back to where you’re from?”

“Where I from, no cheese. I like cheese. Where I from, never eat cow. I like cow.”

“That’s not what I’m–”

“I like bread. What you have, you live.”

Even these moments of intimacy highlight the gulf between the two, entangling their romance with hierarchy and the struggle for survival as women unable to support themselves. Queerness does not cancel out their inequalities but collides with them, producing that beautiful chaos of attraction unfolding where romance and power go hand in hand.

Image Courtesy Fantagraphics.

Yudori further challenges our notions of empowerment and freedom through the ambiguity of Amélie and Sahara’s relationship. With the two characters embracing tenderly on the cover, one might expect a feel-good narrative of love transcending the racism, classism, and homophobia of the time. But Raging Clouds is not that, sprinkling in only crumbs of Amélie’s longing glances and masturbatory fantasies towards Sahara, and her adamant objection to Hans’ plan to sell her.

Amélie’s love for Sahara, while sometimes misplaced, underlies their often cold dynamic of master and enslaved, wife and the other woman. Empowering in isolation, Amélie’s quips take new meaning in relation to Sahara, who doesn’t have the privilege of defying Hans. These imbalances complicate their intimacy: Amélie’s desire can read as imposition framed by the whiteness and wealth, while Sahara’s servitude to Hans places her relationship with him over that brewing romance. Their relationship toes the line between tender and potentially coercive, a love story shaped less by liberation than by the inequities that bind them.

Contrasting Amélie’s contempt for Hans, Sahara’s acceptance of their situation positions her as a non-traditional heroine. She’s not the feminist girlboss we may hope for, one who forcefully escapes slavery and defies all odds for love, but she finds contentment and liberation in making the choice she — not Amélie, nor potentially a 21st-century reader — sees fit. In an era where options for lower-class women of color are dismal, she chooses relative comfort and peace, reminding us that female liberation is case-specific rather than one-size-fits-all. Her decision refuses a clean separation between idealistic queer love and realistic straight domesticity, paradoxically affirming queerness as an identity possible amidst constraint.

“If you were expecting a story that ends with queer girls holding hands and riding into the sunset together … you might be disappointed,” Yudori said on Instagram. Explaining the cultural normalcy of platonic and same-sex intimacy in Korea, she rejects the Western notion that queer empowerment relies on overt labels, on being loud and proud, which, like for Amélie and Sahara, is not always a safe option. In these cases, liberation relies foremost on queer survival.

In that same Instagram post, Yudori reflects on her teen years in Korea, the friendships and gestures forever floating in what she calls the “beautiful chaos” between straightness and queerness. The negative connotation of queerbaiting prompts us to assume that sexual ambiguity comes from a lack of pride, a lack of courage to be one’s true self. “But,” Yudori asks, “can you call entire lives sad just because their choices don’t fit nicely with your categorization of the world?”

Can we impose unsolicited pity on Sahara for accepting her enslavement, even though seeking our idea of freedom would likely leave her worse off? Can we pity Amélie and Sahara for not fulfilling the hand-holding, sunset-tinted narrative we’d prefer to read when doing so would set them up for lives of ostracization and poverty? Overall, Yudori challenges readers to accept her characters’ right to determine their own destiny and personal definition of liberation.

Raging Clouds ends just as it starts, only seven years later: “She looked at the land. It was taken by men. She looked at the sea. It was also taken by men.” Amélie remains a housewife, Sahara still enslaved. It’s disappointing, maybe. But as Yudori explains, “Raging Clouds is, above all, a story of failed attempts — the beauty of not succeeding, not owning, not defining.”

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.