REVIEW: Little Beasts: “Art, Wonder, and the Natural World” at the National Gallery of Art

Installation view of Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World at the National Gallery of Art, Washington (May 18–November 2, 2025). Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

REVIEW

Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World

National Gallery of Art

Constitution Avenue Northwest

Washington DC, 20565

May 18-November 2, 2025

By Anneliese Hardman-Connor

“Care for and empathy of little beasts has a past and a future.” These words narrated by and included in Dario Robleto’s film Until We Are Found: Hymns of the Elements communicate themes central to the National Gallery of Art’s (NGA) exhibition Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World. The exhibition is curated by NGA curators of Northern Baroque paintings and old master prints and drawings, Alexandra Libby, Brooks Rich, and Stacey Sell and is created in collaboration with the National Museum of Natural History, Smithson Institution. Together, nature sketches and scientific specimens are placed in conversation with each other to broach questions of: how do nature sketches and taxidermy, shells, and mounted insects function as both artworks about care and reflections of complex scientific lifeforms? Can the act of creating, conserving, and now exhibiting nature sketches be one that promotes stewardship of all lifeforms, even “beestjes?1”

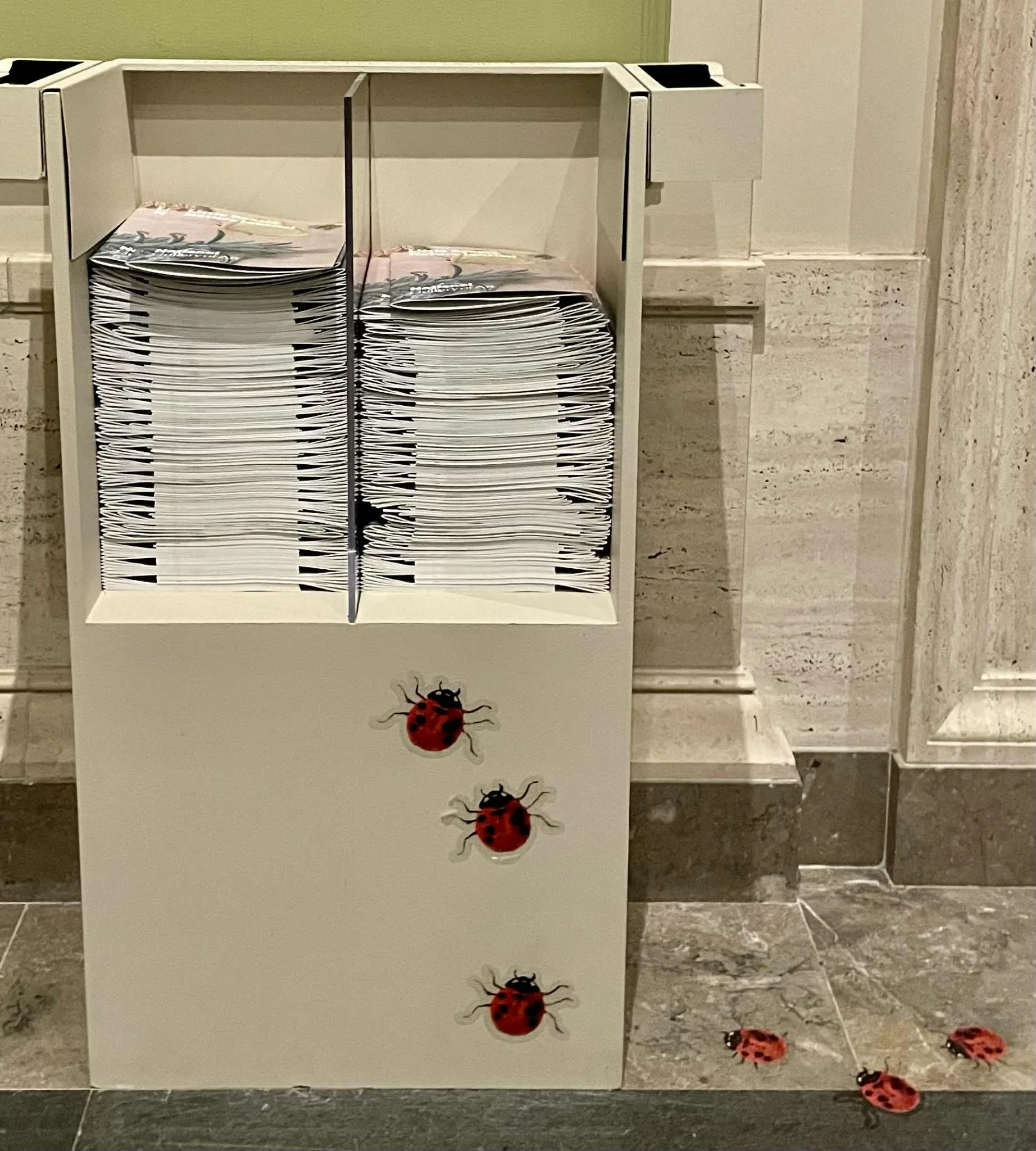

These questions are answered through four exhibition rooms organized by key themes and artists: ‘Joris Hoefnagel and Early Natural History,’ ‘Animal Prints (1580-1650),’ ‘Jan Van Kessel (1650-1670),’ and ‘Dario Robleto.’ Each room is rich with specimens, visual materials, and museum interactives, suitable for engaging viewers of all ages. Visitors enter the West Building of the NGA, proceed through security and are immediately guided from the museum’s entrance to the special exhibition by a ‘loveliness’ or grouping of vinyl ladybug stickers. The entrance itself connotes pages of a nature journal, visually cuing visitors for a museum experience that draws on practices common to natural history and art museums. Upon entering the exhibition entrance, the loveliness of ladybugs directs visitors towards nature journals that facilitate learning activities as viewers walk through the exhibition. This playful introduction primes visitors for an experience that conjures feelings of wonder for the natural world that Dutch sketch and still life artists also felt during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Installation view of Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World at the National Gallery of Art, Washington (May 18–November 2, 2025). Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Lovlieness of ladybugs leading guests to nature journals as part of Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World. Photo by Anneliese Hardman-Connor.

The first exhibition room introduces the origins of natural history through illustrations by Hans Hoffman and nature books by Joris Hoefnagel. Watercolor works by Hoffman are paired with taxidermy mounts from which the subjects of the works are based on. Pairing mounts and watercolor works together illustrates how artists created works conceptually inspired by the natural world. For example, the taxidermy woodchuck (lent by the National Museum of Natural History, Smithson Institution) dates to the Victorian era when mounts were often filled with rags and sawdust.2 This practice led to overstuffing in some cases and a generally round appearance to mounts. As a result, the watercolor based on such a mount also appears chubby.

Installation view of Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World at the National Gallery of Art, Washington (May 18–November 2, 2025). Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Centrally displayed in the same room are art books, titled Four Elements, by Antwerp based painter, printmaker, and miniaturist, Joris Hoefnagel. Four Elements was visually informed by taxidermy, study skins, and other specimens. Created as a personal project, it is a series of four volumes each named for a classical element, containing images of the animals who live in that realm.3 Each book is not just inspired by natural elements but also contains parts of actual specimens. Hoefnagel illustrated his works by transferring pigments and patterns from the original specimen. Adjacent to information about Hoefnagel’s process are the organic materialities used by Hoefnagel in his works including, cochineal, sourced for red pigmentation, malachite, the basis for greens, and indigo, used to make blues. Showcasing Hoefnagel’s technique acknowledges the reliance of artists upon the natural world to physically create artworks as well as inspire subject matters.

Installation view of Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World at the National Gallery of Art, Washington (May 18–November 2, 2025). Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Exhibition room two continues to highlight artist utilization of scientific specimens to draw and paint from nature but also showcases the inverse importance of visual artists to increasing scientific knowledge of nature. Centrally placed in room two is a moveable wall constructed specifically for the exhibition featuring etchings of animal skeletons by Teodoro Filippo di Liagno Napoletano. Created by Napoletano while in Florence, Italy, his Incisioni diversi scheletri de animal (Various engravings of Animal Skeletons) consists of 21 plates each documenting the specimen collection of German physicians, botanist, and art collector, Johannes Faber.4 Napoletano ‘s etchings were widely disseminated and contributory for the field of comparative anatomy which emerged during Europe’s Scientific Revolution (1543-1687). While mentioning that the dissemination of Napoletano’s etchings trace trade routes of the era, more information about who would have seen these etchings and utilized them for scientific purposes could have clarified their importance. In addition, information about how specimen collections were acquired would have added depth to the sociohistorical significance of such collections like that of Johannes Faber.

Installation view of Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World at the National Gallery of Art, Washington (May 18–November 2, 2025). Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

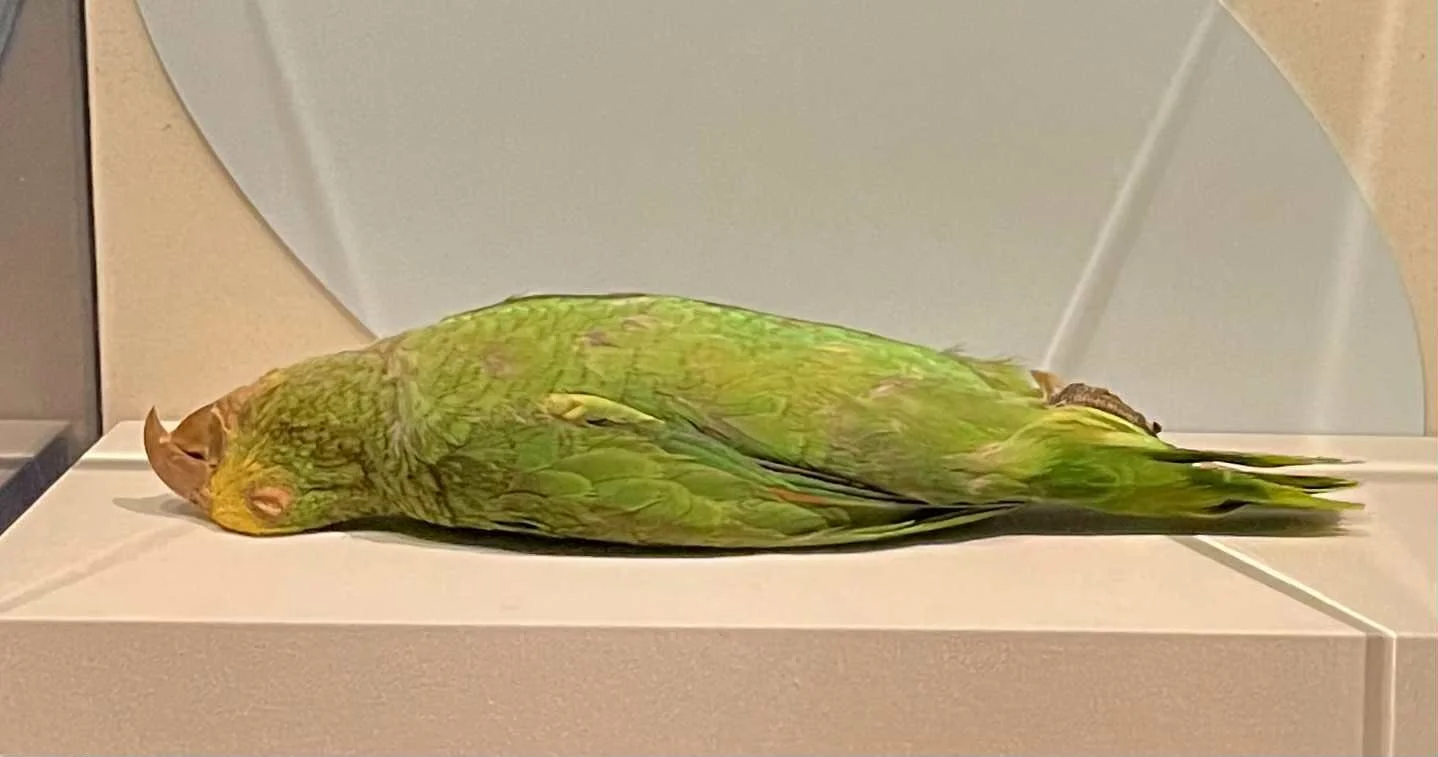

Exhibition room three discusses adverse impacts resulting from disseminating physical rarities and specimens during the 17th century. During this era of global trade and colonialism, collectors were eager to import and possess the natural world and for artists to document private collections for social status. Works by Jan Van Kessel are displayed in this room linking paintings of rarities and still life works with modern day exploitation of animal populations. For example, a study skin of a yellow-headed Amazon parrot, currently considered endangered because of the exotic pet trade is presented alongside Van Kessel’s Concert of Birds and Noah’s Family Assembling Animals before the Ark, c. 1660. This latter oil on canvas was painted in homage to his grandfather, Jan Brueghel the Elder’s 1613 The Entry of the Animals into Noah’s Ark which was painted by observing the Hapsburg’s personal palace zoo. Throughlines of the exotic pet trade dating to the 17th century and the modern period illustrates how the original dissemination of nature paintings by artists like Van Kessel have continued to have an ecological impact. While visually showing these connections, the exhibition could have more explicitly explained the connection also through labels.

Unknown Amazona ochrocephala (Yellow-headed Amazon parrot), study skin. Loan courtesy of National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, USNM 257950. Photo by Anneliese Hardman-Connor.

Jan van Kessel the Elder Noah's Family Assembling Animals Before the Ark, c. 1660 oil on panel overall: 65.4 x 94.5 cm (25 3/4 x 37 3/16 in.) framed: 83.19 x 112.4 cm (32 3/4 x 44 1/4 in.) The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland (Museum purchase, 1946), 37.1998

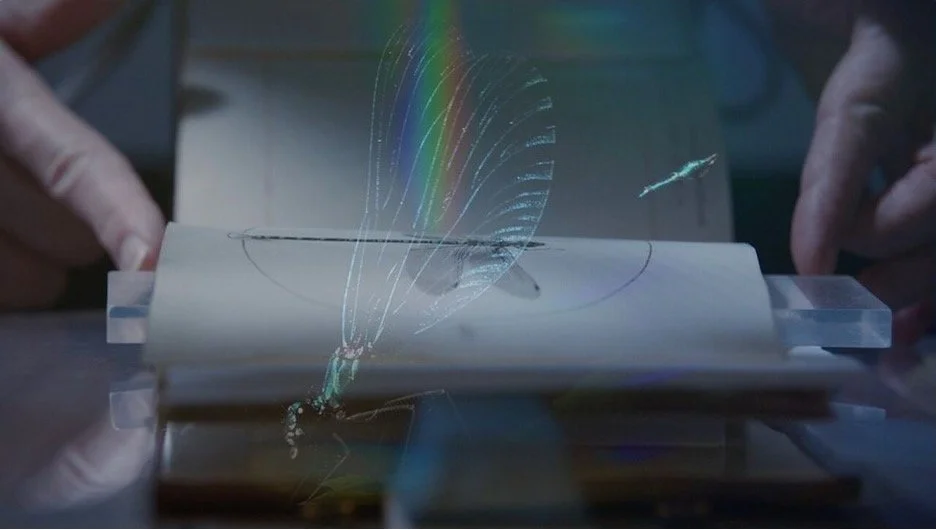

Visitors end their viewing experience by watching Dario Robleto’s film Until We Are Found: Hymns of the Elements, (which ran on the top of each hour for 43 minutes). The film presented NGA conservators preserving and caring for the nature prints and books in their collection. While interesting to see the behind the scenes of NGA’s conservation studio, the film portrayed an overly positive view of the NGA and of the field of conservation and collecting. There was no mention of museums sharing in a legacy of colonially collecting objects and often hoarding objects. There also was no mention of the sometimes-unethical ways that conservators refuse communities of origin interaction with objects on the basis that the object could be broken. Instead, only themes of how conservators pass down memories from the past was focused upon.

Dario Robleto Until We Are Forged: Hymns for the Elements, 2023–2025, single-channel UHD video, color, 5.1 surround sound, 43 minutes. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Little Beasts is an insightful and groundbreaking show for its methodology of placing specimens from the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution in conversation with nature sketches and paintings. Placing taxidermy within an art museum setting validates taxidermy as an artform in a way that it is typically not afforded. To strengthen this connection, a history of taxidermy’s artform could have increased appreciation for how it has changed over time and remains a form of creative expression throughout the United States. Included in the exhibition was a variety of aquatic species, birds, and mammal taxidermy mounts, alongside insect specimens that caused the viewer to question why the title of the show was limited to ‘little beasts’ instead of just ‘beasts.’

Playful and very engaging through a variety of exhibition interactives like nature journals, questions on labels, and touch screen versions of art, the exhibition was sometimes not critical enough of the colonial implications of collecting and documenting nature during the 16th and 17th centuries. For example, a curiosity cabinet was exhibited as part of the show and analyzed as an artform and place for holding small shells and minerals yet did not mention from where these small treasures were acquired. Language was also vague about how specimens were collected for artists to observe. Including this information would have given a larger context for viewers curious about how the objects within the museum’s exhibition came to be. Despite these knowledge gaps, the show is a fruitful exploration of how natural history, and the visual arts mutually inspired each other during the 16th to 17th centuries, also causing viewers to consider their continued commingling as disciplines today.

Attributed to Boas Ulrich Cabinet, c. 1595/1600 or later ebony and ebony veneer over spruce and walnut, with silver and gilded silver mounts overall: 33.7 x 35.1 x 29.2 cm (13 1/4 x 13 13/16 x 11 1/2 in.) overall (base): 1.3 x 35.1 x 29.2 cm (1/2 x 13 13/16 x 11 1/2 in.) National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection 1961.9.185. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

Anneliese Hardman-Connor is a curator, lecturer, and museum enthusiast specializing in Southeast Asian art histories. Currently, she is pursuing her PhD in Art History at the University of Illinois Chicago with a focus on contemporary Cambodian art. Her dissertation project explores art that reflects relational changes of Southeast Asian environments and culture. You can find her other publications on Art & Market, Athanor, and Fwd: Museum Journal.

FOOTNOTES

1 Beestjes translates to little beasts in Dutch and came to refer to local Dutch and other unfamiliar species of insect that were once overlooked in the Netherlands, but during the 1500s were popularly studied and collected. Introductory Exhibition label, in exhibition “Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World” at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, seen on August 8, 2025.

2 “A Brief, Gross History of Taxidermy,” Museum of Idaho, para. 5, https://museumofidaho.org/a-brief-gross-history-of-taxidermy/.

3 The Four Elements label, in exhibition “Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World” at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, seen on August 8, 2025.

4 “Filippo Napoletano: A Baroque Master of Landscape, Etching, and the Unconventional,” Nice Art Gallery, para. 8, https://www.niceartgallery.com/artist/filippo-napoletano.html.

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.