REVIEW: Scott Burton, “Shape Shift” at Wrightwood 659

Installation view of Scott Burton: Shape Shift, at Wrightwood 659, 2025. Courtesy of Daniel Eggert (@DesigningDan).

REVIEW

Scott Burton: Shape Shift

Wrightwood 659

October 3 – December 20, 2025

By Hunter Scott

Scott Burton the artist has multiple points of entry. One may come to him by way of his work as a performance artist, a conceptual artist, a post-minimalist, a furniture designer, a public sculptor, a curator, or an art critic. And yet to brush up against Burton and reduce him to any one of these identities above is surely to miss the point. Scott Burton is a verse.

Scott Burton the exhibit also has multiple points of entry. Currently occupying the top two levels of Wrightwood 659, one may enter Scott Burton: Shape Shift either on top (which is to say the fourth floor) or from below (the third floor). Thus, in keeping with the artist’s versatility, there is no wrong way to do Scott Burton. As curated by Jess Wilcox and Heather A. Smith, the exhibition coyly offers entries as exits and exits as entries, hinting at both the homoerotic subtext of what is to come and the queer, boundary-dissolving relations between people and objects that so fascinated the artist.

Mounting the first career-spanning retrospective of the genre-bending artist in the US in over four decades, Wilcox and Smith’s Shape Sift invites viewers to explore the different facets of Burton’s career as they transform into each other, blurring the boundaries of stable categorization in order to resist the fantasy of a fixed, essential identity. Beyond entries that are also exits, in Shape Shift viewers will share encounters with stools that are tables, tables that are lamps, furniture that is sculpture, and curtains that are windows.

Installation view of Scott Burton: Shape Shift, at Wrightwood 659, 2025. Courtesy of Daniel Eggert (@DesigningDan).

The aptly-named exhibit therefore embraces the fluctuating nature of identity and its ability to take new forms, be new things. Neither solely one category or the other, the exhibit highlights the more flexible dialectic modality of being both/and. That is, to borrow the title of art historian David J. Getsy’s recent monograph on Burton which serves as inspiration for the show, the works in Shape Shift exhibit a certain “queer behavior” as they move from one identity to another, encompassing both but reducible to neither.

The exhibit argues that Burton drew upon his experience as a queer man and used shape shifting as both a survival and an aesthetic strategy in order to navigate the rampant homophobia in and outside the art world from the late 1960s until 1989 when he passed from AIDS-related complications. Some of Burton’s earliest works on display most overtly capture his queer strategy.

Scott Burton, Study pose for Individual Behavior Tableaux included in "Documenta 6," 1977. Polaroid 4 1/4 × 3 ½ inches (10.8 × 8.9 cm) Scott Burton Papers, II.75. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York © 2024 Estate of Scott Burton/ Artist RightsDigital Image © The Museum of ModernArt/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

For example, in adjoining sections titled “Early Conceptual, Performance and Installation Work” and “Stage Performance,” the exhibit presents a selection of photographs, ephemera, and a rarely-seen video that make visible the link between queerness and movement at the heart of Burton’s shape shifting. In these works, Burton staged the moving male body in various states of undress to signal its homoerotic potential. Whether walking nude down a dark street at night (as he did for his Self-Work: Dream performance in “Street Works IV” [1969]) or choreographing a slow-moving man dressed only in heels to emulate poses the artist encountered at bathhouses and other public sex spots (as he did for Individual Behavioral Tableau [1980]), the exhibition reveals how Burton drew upon gay male sexual cultures and, in particular, their practices of cruising for inspiration. For it is in the art of cruising–of erotically moving through public spaces with plausible deniability so as to camouflage oneself to one audience while simultaneously signaling one’s sexual availability to another–where shape shifting takes one of its forms.

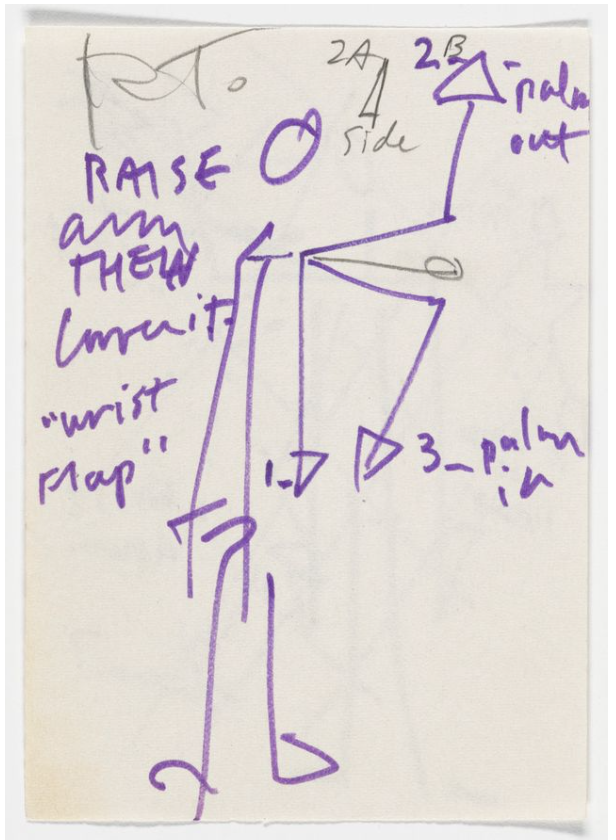

Scott Burton, Individual Behavior Tableaux choreography note, ca. 1980. Scott Burton Papers, II.91.4 3/16 × 3 inches (10.6 × 7.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art Archives, NewYork. © 2024 Estate of Scott Burton/ ArtistRights, Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / ArtResource, NY.

Given that one aspect of shape shifting, then, is the ability to remain hidden in plain sight, a spectator of Shape Shift risks overlooking one of the secret stars of the show. Tucked away in a vitrine that fleshes out Individual Behavioral Tableaux (1980) are choreography notes from Burton’s archive that have never before been displayed. In these hand drawn instructions, Burton illustrates the erotic poses his model will take for the performance. His notes abstract his male model into a stick figure. In other words, in Burton’s choreography notes, the human body takes on a new shape as its representation shifts into pure geometry. A human leg, now depicted through lines, terminates in a triangle that suggests a foot. Through Burton’s formal abstraction and the shared lexicon of anatomy, the figures of Burton’s drawing appear to shape shift into chairs before our very eyes. Or, as Burton himself once noted, “You could say that people are like furniture. They take different poses and suggest different genders.”

While the spindly legs and club feet of Burton’s choreography notes might recall–or, depending on the order in which one cruises the exhibit given its multiple points of entry, foreshadow–Burton’s iconic Bronze Chair (1972, cast 1975), it is the Queen Anne-style armchair’s near neighbor that best exemplifies the anthropomorphizing quality of Burton’s queer shape shifting. In a private northerly corner, as if slightly secluded from prying eyes, one happens upon Two-Part Chair (1986). Composed of two self-supporting tetris-like shapes of hard granite, Two-Part Chair, on first glance, appears to have nothing in common with Burton’s interest in performative movement and queer sexuality. Indeed, from certain angles, it may strike viewers not as furniture but as an innocuous post-minimalist sculpture. And yet, as one circles around it, its masculine shapes shift and its evocative form emerges, albeit in highly abstracted fashion. The back of the chair, perched behind and leaning into the bent-over seat suddenly resembles coitus a tergo, sex from behind.

Scott Burton, Two-Part Chair, 1986. Granite. Photo by Hunter Scott.

Despite its allusion to an explicit homosexual sex act and its cold post-minimalist aesthetic, Two-Part Chair isn’t some unfeeling proposition, as cruising is too-often accused of being under the moniker of impersonal sex. Rather, for Burton, who once analogized his oeuvre to the star-crossed couple of high art and design when he described his work as “sculpture in love with furniture,” it is the boundary-transgressing capacity and relational affect of love that is at the heart of his work. After all, one-half of Two-Part Chair cannot stand on its own; it requires its other half to self-support, to exist.

In this light, Shape Shift is at its best, its most queerly romantic, not only when the objects before us shape shift from one thing to another, but when we shift our relation to them. The exhibit rewards a type of alterity on the part of the viewer, the ability to be open to radically unstable ontologies and new interpretations that come from a place of love. In Shape Shift, it’s not just the sculpture that transforms into furniture, but the viewer themself who undergoes transformation, shifting from a once-passive spectator into an active participant. In one final act of shape shifting, the exhibit, as its strongest, becomes theater.

With Wrightwood 659 as its stage, Shape Shift reaches its climax when our bodies and Burton’s body of work converge. After cruising past sections that explore his roles as curator and public artist, one reaches a private room dedicated to “The Gravitas of Stone.” Here, viewers are encouraged not only to reflect on the materiality of stone–a medium commonly used in memorial monuments and public art because of its durability–but to feel it. Four empty seats beckon. Generously, they ask us to use them, to rest on them.

Installation view of Scott Burton: Shape Shift, at Wrightwood 659, 2025. Courtesy of Daniel Eggert (@DesigningDan).

Two-Part Chaise (1989) is particularly alluring in its solicitation that suffuses the melancholic with the erotic. Produced in the same year that Burton’s life was cut short by AIDS, its vacancy and granite materiality both recall and memorialize absence, conjuring memories of those who can no longer enjoy its pleasures. And yet, its abstracted angular pose also recalls the nude in repose. Two-Part Chaise is a body that asks you to join it, to lie with–or, rather on–it, to throw your legs up in delight as your body shifts its shape to fit its own.

Should you choose to lie down with Two-Part Chaise, as I did, you will get a glimpse out a low-hanging window. From this perspective, on this sculpture that is a chair, on this art that is design, the outside is brought inside for the receptive body who is both observer and performer.

In Shape Shift, when boundaries are crossed and identities are blurred, one may not leave as the same person they came in as.

______________

Hunter Scott (he/him) is a PhD student in the Department of English Language and Literature at the University of Chicago.

Like what you’re reading? Consider donating a few dollars to our writer’s fund and help us keep publishing every Monday.